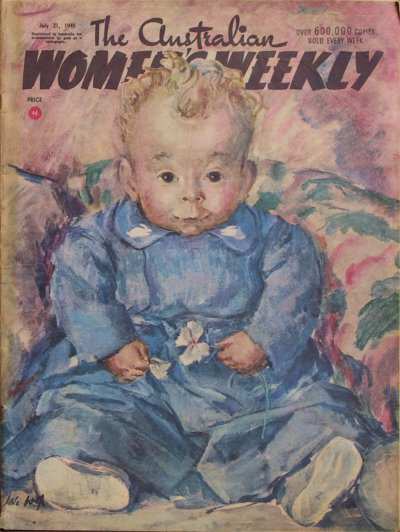

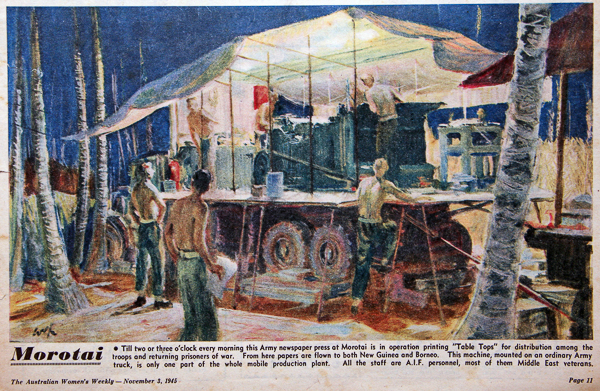

The follwing copy, written whilst in Morotai was the basis for a story published in The Australian Women’s Weekly: 1945 ‘Soldiers in North talk and dream of home.’, The Australian Women’s Weekly (1933 – 1982), 8 September, p.17, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47246573

Morotai, Thursday 16th August [1945]

It was pretty certain on Friday the 10th of August that the war was over. But the wild exuberant lead that flew around to celebrate the peace was just as vicious as that of war. Ironically, peace too, brought its casualties. The spontaneous rattle of machine guns and rifles was answered by the bopping of the Bofors and the slicing of the searchlight batons beating time across the sky. But the tension was gone and there was singing and drinking and yelpings of joy. And there was sentimentality galore. Three days it lasted. By Monday the boys had steamed right off and official peace was accorded no more than just a passing nod. In the night a few tracer shells moved in slow red perforations across the night and no one cared. It was more important and more depressing to contemplate the months yet to be served before demobilisation became for each a real returning to the ways of peace. Things were normal then on Monday. The hangovers were lifting and the cooks just cooked while batmen batted. In the evening at the pictures I attended, the troops stoically accepted the acrobatic antics of warrior Errol Flynn. The ceremonial tracers and searchlights moved on. The Australian Comforts Fund came good with a hamper for each and the thousands of plum-puddings are waiting on the spoon. Jube-jubes, peanuts, and peaches for the boys. A free bottle of beer has been promised.

But after all the shouting the life and background for most of the army personnel is still the same. The jungle is still green and thick and the Celebes Sea is just as ever.

Over there in Northwest Borneo the country is still smothered with gross fat trees in all shapes and sizes. You backyard fernery folk would still goggle at the orchids, creepers, staghorns, and palms – herringbone ferns and bracken like you have at home, but taller than a man!

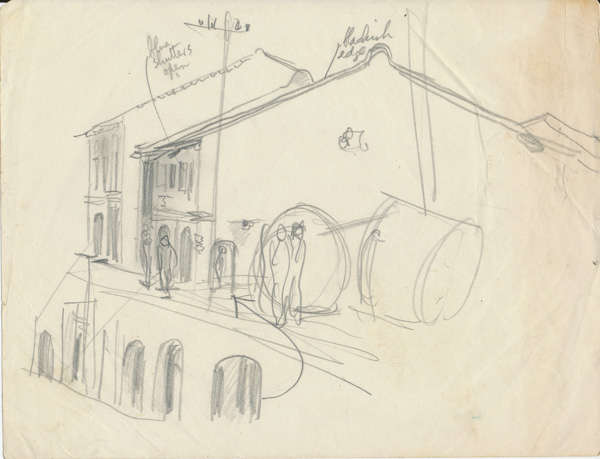

Thanks to the zestful bombing of the RAAF and to the shelling by the navy, all the shopping centres of all the towns and villages have gone with the wind. One can only surmise what must have been the beauty of pre-bombardment Victoria Town on Labuan Island. The fragments of pale blue plastered walls, the heaps of bright red bricks and tiles, the remains of Chinese architectural devices, the broken retaining walls of the canal behind the shops, the gaunt and shattered trees, the only two surviving brick buildings, the isolated clock tower, an aloof and well-proportioned symbol of the town remain to testify to its one-time charm. What is left is just a ghost. The bricks and bones that were once its substance have been bulldozed off and used as filling on the airstrip. Victoria Town is buried there.

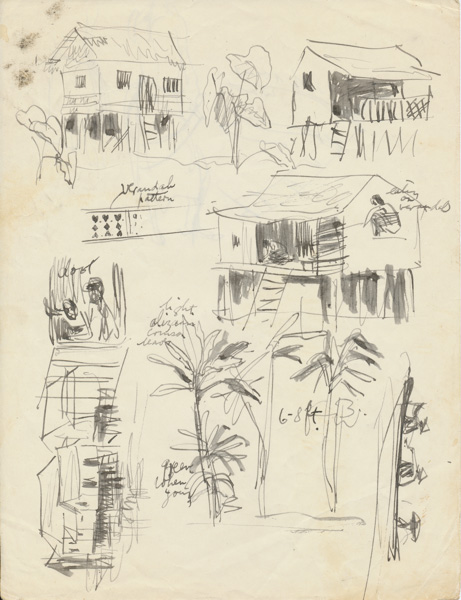

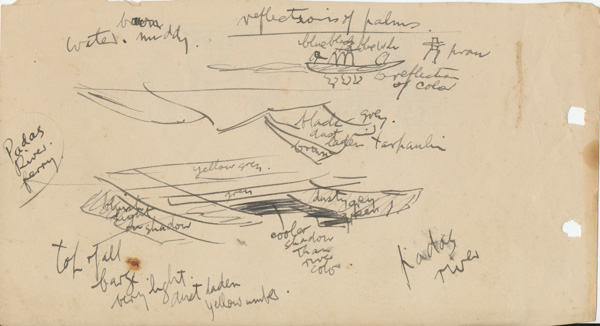

It is a tedious four and a half hours journey by landing craft to Brunei, your doldrums unrelieved by the sight of anything of interest and intensified by the down pouring blast of the Borneo sun. Heaven help Venice if Brunei is, as some allege, “The Venice of the East”. Only a real estate agent could have thought that one up for such a squalid grey collection of native houses. They squat weakly on their legs over the evil-smelling mudflats of the stream. Certainly there is a touch of carnival in the comings and goings of the children in their praus, and in their singing, – high pitched notes that float smoothly on the river and the ooze. Tatter clothed natives pick and scratch in the rubble of the town.

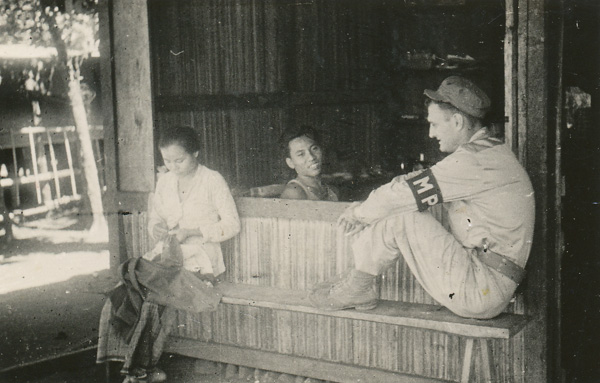

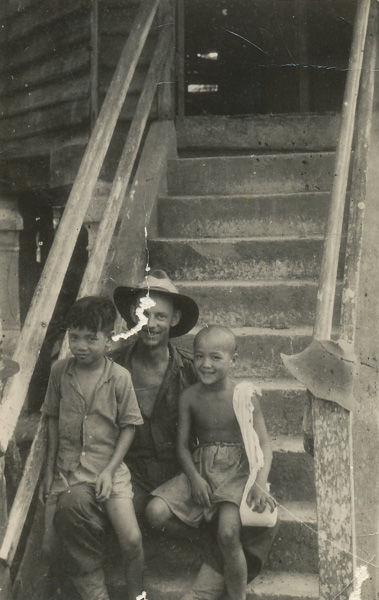

Surprisingly the road to Tutong bursts into twin concrete strips like tracks into a suburban villa garage. The interminable bowing and saluting of the natives is a hangover from the rigourous Japanese domination. Every thatched hut has more than its quota of sparkling little nippers, mostly nude, who wave and salute like their elders. From the more knowing you get thumbs-up and victory signs.

The road loses itself on the beach and the beach becomes the road. The China Sea swishes on the beach and the breeze is cool. A continuous line of casuarinas encroaches on the sand and reminds the boys of home.

Far ahead the smoke of the burning oil wells of Seria throws up the dull blue shape of an apparent mountain range. Closer, the sky darkens and the wind is quiet in the ominous gloom cast by the rolling smoke that dims the sun to the ignominy of a mothball hanging in the murk. Great jets of flame roar like Gargantuan blowlamps, the earth rumbles, and the trees are smothered in soot and oil. It is a black and white photo with fires in the middle. Australian army engineers are putting them out.

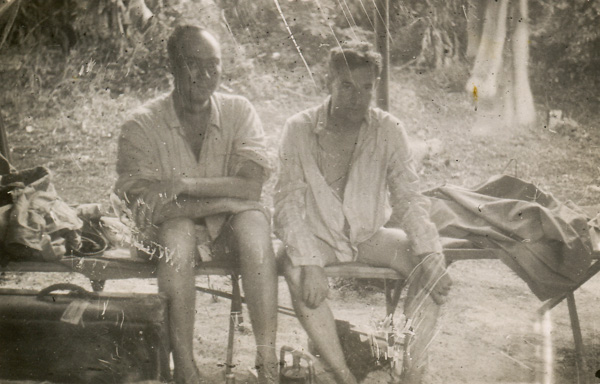

Personnel of the 20th Bgde. live a smooth existence at Kuala Belait. Here they share such terrors of war as laid-on gas and water, cricket and swimming on the beach, and offices, reading rooms, and a ping-pong in the homes and clubs of the pre-war oil executives. “A great war”, they used to say, but they’re pleased to see it over. The entrance to the erstwhile market is nice and handily flanked on one side by the local jail and on the other by a notice board bearing dire Army proclamations in English, Chinese and Malay. A few blackened beams and the fire-blued skeletons of a thousand bikes form this cemetery of a street. Malays and Chinese still shuffle up and down the road, or sit passively in the shade to watch the kids play and screech just as they do in Redfern or Fitzroy. In front of three tired shops – the only ones left – tiny silver fish are drying on sheets of corrugated iron in the sun.

From a house comes the brittle tinkling of an untuned piano; someone is playing with one or two fingers a Chinese song which strangely lapses into a few bars of “Way Down upon the Swanee River”. If you get to know little Peggy Ho and you ask her nicely, she will sing in her sweet little voice “I’ll always call you Sweetheart”. She is only 12 and very tiny and in some way her performance is very touching and it makes you think of all the children and of home. Peggy learnt that song and a few others while the Japs were here and when to speak English at all was indeed dangerous. Before they came she knew only her ABC and her family and friends have secretly taught her so much. What could the Japanese do with people like that?

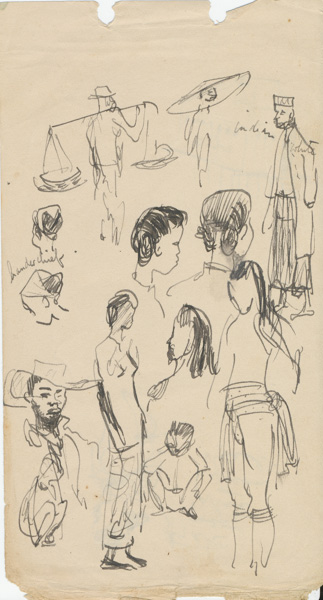

You go to Limbang by barge through twisting aisles of water palms and mangroves. The silence is broken only by the roar of the engines and the monotony of the scene is varied by the appearance of an occasional prau which slides past and is left dancing on the wash behind. The paddlers in their conical straw hats disappear around the bend.

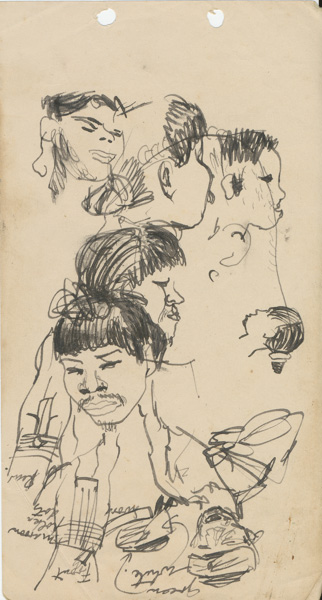

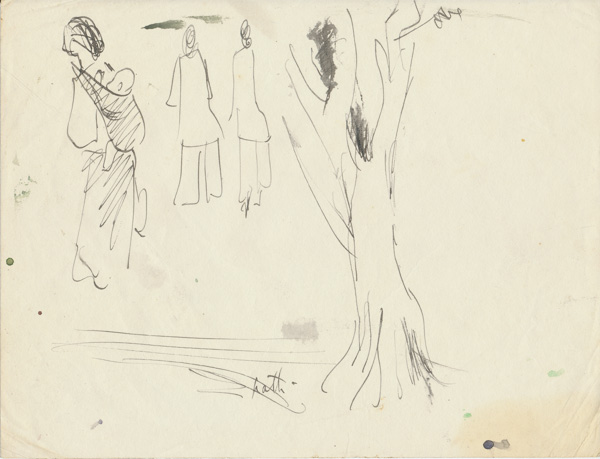

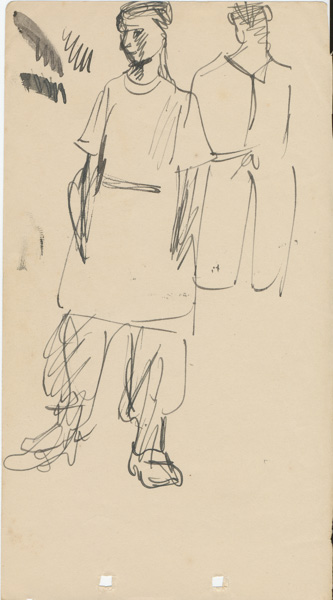

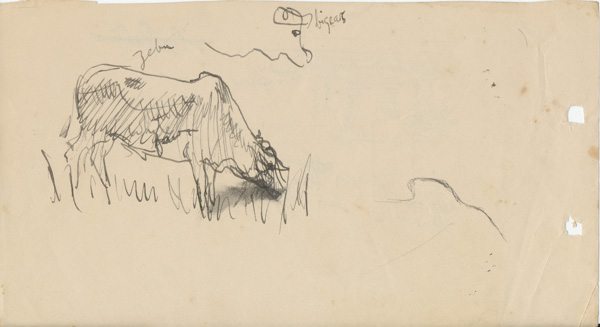

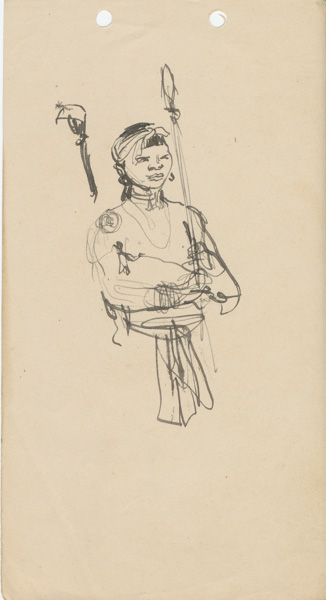

Limbang is the country of the Dyak. He is a real native of Borneo! You are conscious of a shock – your preconceived ideas of him were sadly naïve. Are these exquisitely feminine looking beings the bogeymen of your childhood days? It is unbelievable. Beautifully proportioned, sleek as a pear, you must admire their bodies. Here are Grecian marbles modelled in miniature and clothed in flesh of the lightest coffee hue and tattooed with the green scrolls and mystic patterns on the throat & shoulders. Their long hair is tied up with a strip of coloured cloth and the sun shines bluish on the fringe across the forehead and on the loopings of the spiral pointed bun. Throat bands, armlets, silver bangles just above the calf, and a loin cloth cunningly tied complete the peaceful ornamentation. But their swords and spears are razor sharp, their blowpipes silent and deadly. Many a Jap straggler’s head has been lopped and smoked for their mantelpieces at home. A useful ally to have even if he is not, patrolmen will say, so blooming hot in an open fight.

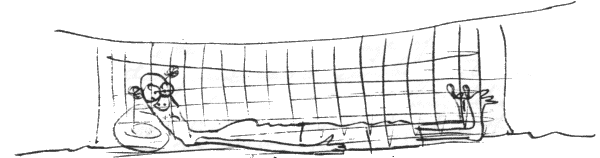

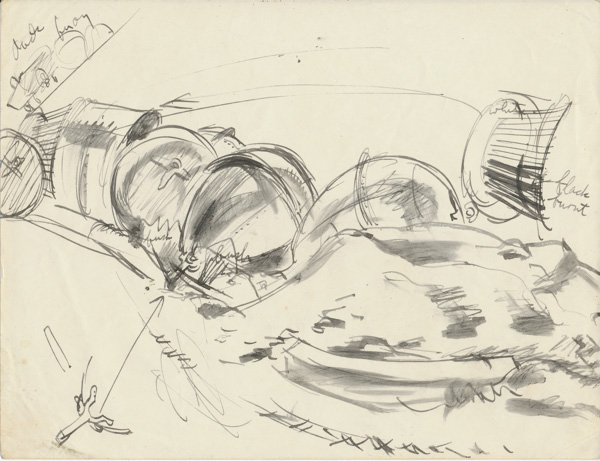

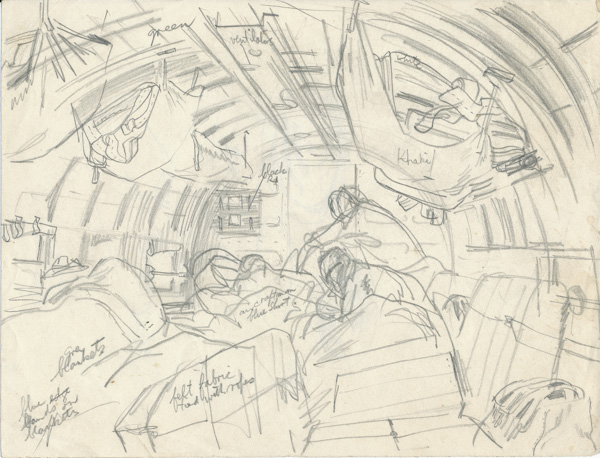

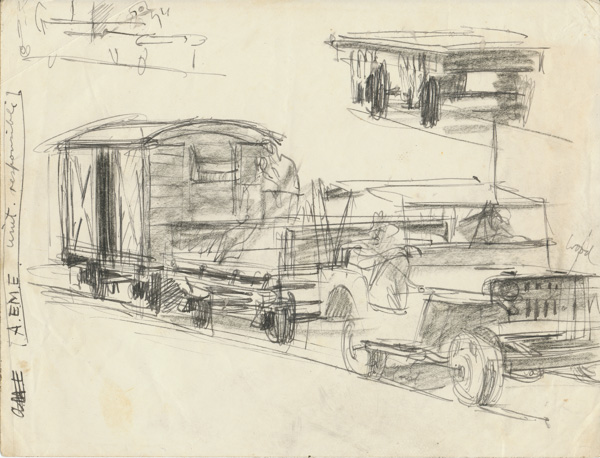

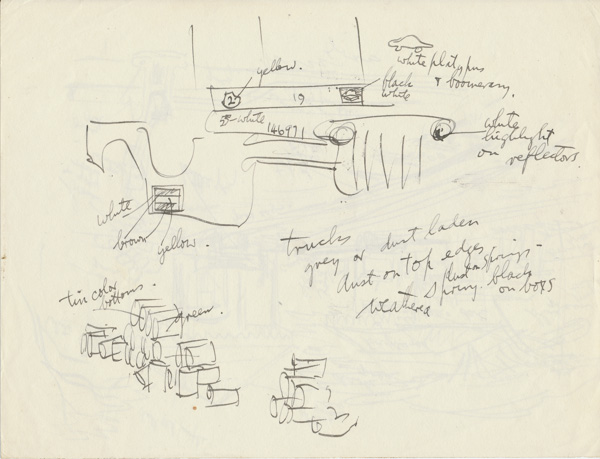

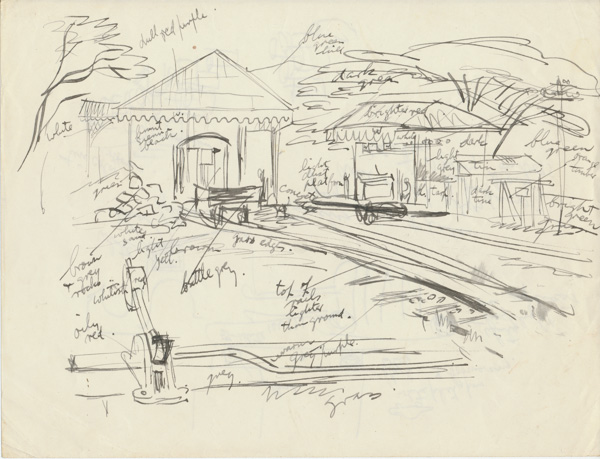

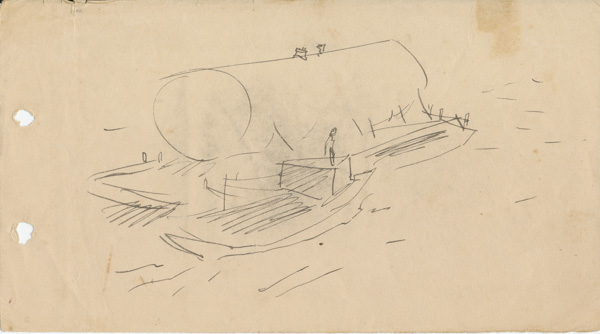

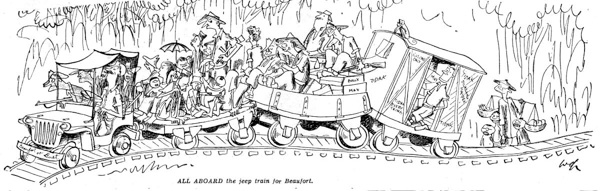

From Labuan another four and a half hours of sitting on a barge like a redhot waffle iron will bring you to the area occupied by the 24th Bgde. This is the land of the celebrated jeep train. Steam engines used to haul the train from Weston to Jesselton but on their hurried way out the Nips did their best to incapacitate the locomotives and the RAAF filled the boilers full of holes. So the engineers put iron tyres on the jeeps and shoved them on the rails and hooked the trucks behind.

The light narrow gauge line leads the train through disused paddy fields, through long and delightful tunnels of tropical green. The rubber trees meet in an arch overhead and the undergrowth, unhindered for the last three and a half years, forms walls of fern and palm and lasiandra whose purple flowers brush your body as you pass. For long stretches the track is carpeted with grass and only the polished rails indicate the way ahead. An intimate green pathway over which trucks clunkety-clunk and we lack only the great asthmatic puffing of the real thing. Natives stand aside for us to pass at intermittent clusters of houses, or at a real station, we disgorge bodies and rations to the babble of the Chinese and Malays.

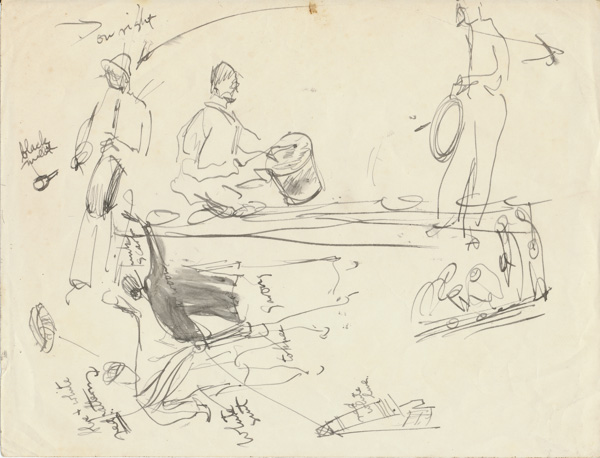

At Beaufort the army put on a carnival day for the children of the district. The natives swarmed in by train, in boxcars and flat-tops. They squatted and huddled together tight as a bunch of grapes and quietly soaked in the drenching rain. In the boxcars native orchestras “gave out” and were “in the groove” in several different tunes. The penetrating boom of the gongs and the light melodic harmony of the gamelins (a xylophonic saucepan affair) burrowed through the dusk and rain. It was a great day for Beaufort. The children laughed at the soldiers and the soldiers laughed at the natives. Pillow fights and obstacle races, lolly-water and fireworks, Malay dances and Chinese singing, jeep rides, speeches and fraternisation, Miss Beaufort competition and ceremonial tea drinking – it was all there. British administrators considered with gloomy foreboding the Australian “spoiling of the native”. At 11.30 p.m. they straggled home – grandpas, grandmas, dads, and mums with sleeping kids swung in “cuddle seats” made of gaily coloured scarves.

There is nothing more to say. In all the talk of Borneo it is only home, and how quick the five-year men can get there that matters. This is THE topic, whether with the boys on patrol, or with the wallahs at the base. Points scores and probabilities of departure times are studied and discussed like form guides, And it shouldn’t be long before many homes have their men back for good.

(Alternate paragraph on different paper)

Of all the talk in Borneo it was, and still is, only home and how quickly the men can get there that matters. This is THE topic, with both the boys up front and the wallahs at the base.

Naturally five-year men will be first and points scores and probabilities of departure times are studied and discussed like form guides. News of the POWs of the Eight Div. Is expected hourly and the long awaited reunion with them is imminent.

Yes. Very soon many homes will have their men return for good.

Love Willie

Love Willie but am meeting with no success as they seem to be made only for personal use and in any case I am stuck for means of transport to where I might pick one up. There is actually nothing about – one has to realise that 3 weeks or so ago this area was still in Japanese hands and that the RAAF have blown all the shopping areas to bits in all the places I have been to. Naturally all the saleable commodities went with the wind as well.

but am meeting with no success as they seem to be made only for personal use and in any case I am stuck for means of transport to where I might pick one up. There is actually nothing about – one has to realise that 3 weeks or so ago this area was still in Japanese hands and that the RAAF have blown all the shopping areas to bits in all the places I have been to. Naturally all the saleable commodities went with the wind as well. you put the kerosene if you can get any in here.

you put the kerosene if you can get any in here.![[Jeep train study, Borneo]](http://wepidgeon.com/pidgeonpost/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/WEP-45-A-3376-D.jpg)

![[Study, Dyak warrior, Limbang area, Sarawak I]](http://wepidgeon.com/pidgeonpost/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/WEP-45-A-3931-P.jpg)

![[Study, Dyak warrior, Limbang area, Sarawak II]](http://wepidgeon.com/pidgeonpost/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/WEP-45-A-3932-D.jpg)